This is part of a series originally created on LinkedIn, where we start thinking differently about others we might have dismissed as “Difficult Colleagues.” But we have a serious need to rethink our relationships with them and the situations we’re in.

Understanding that we might be wrong is a distinct possibility that we usually overlook, as we are typically the heroes in every story we tell.

For the previous posts in the series, click here:

- Difficult Colleagues? Introduction to the Series

- Difficult Colleagues? Possibility 1 – Paradigm Shifters

- Difficult Colleagues? Possibility 2 – Gender Behavioral Differences

- Difficult Colleagues? Possibility 3 – Fundamental Attribution Error

Unfortunately, I’ve never been a model employee – ask any of my former managers. Part of my problem was something I wasn’t even aware of – how my brain chemistry worked to my detriment.

Growing up in an emotionally abusive family, it was never safe for me to discuss my true feelings about anything with anyone. My sense of safety came only when I pulled my inner self away from my abusive parent.

This left me with a highly triggerable fight/flight/freeze/appease response inside my amygdala forever afterward. My MO was to “freeze.” As soon as a discussion turned risky, my brain retreated into a mental “safe zone” that I had created in my mind, while remaining physically in the same spot. I could withstand the barrage of negative abuse while my mind was relatively free from hurt. [You can read my story, learn about my passion for creating well-working teams, and learn more about how our brains rewire our triggers inside our workplaces here inside my Medium account.]

However unintended the abuse was, it left me with future problems in relationships. Especially unfortunate were my relationships with my bosses. But I never saw these instances as my own learned behavior. Many years later, I understood these discussions were really the give-and-take of brain neurochemicals. We (my managers and I) were complicit in “Conversational ‘Un’Intelligence,” creating lose-lose or win-lose outcomes: we were Difficult Colleagues to each other.

Understanding Conversational Intelligence and the Neurochemicals We Give Each Other Changed That!

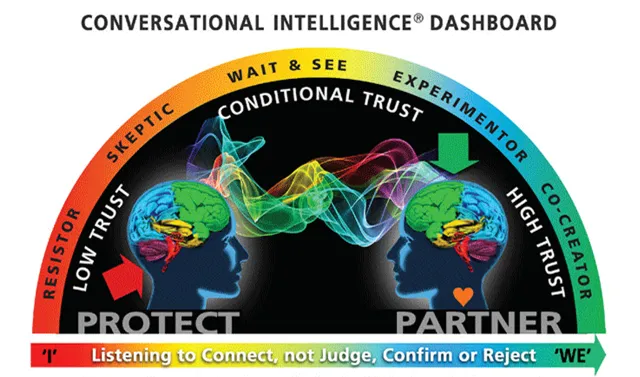

Conversational Intelligence concerns regulating the neurochemicals inside our bodies that we give and take from each other during discussions. When someone experiences good vibes with others, we give them the connection, pleasure and calming neurochemicals oxytocin, dopamine, endorphins, serotonin, and GABA, which are then reciprocated back to us.

But for a person who has been highly traumatized in relationships, our neural pathways stand at the ready to secrete more cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline – the bad neurochemicals, keeping us in a constant state of arousal and stress. Unfortunately, we add this distressing mix of neurochemicals inside our tension-filled conversations, and our partner in the conversation reciprocates them back to us. We have just become Difficult Colleagues to each other.

We can grow in our ability to navigate these situations when we can stop a discussion that has the potential to trigger us and give the other person in the conversation the ability to be heard well, at another time. Then we can enter into one of the highest forms of conversation: a co-creative discussion.

Listen to the late Judith Glaser’s definition of Conversational Intelligence (courtesy of the CreatingWe Institute). Transcription DNA can rewire our brains, one conversation at a time.

”What’s Going On Here?”

What would happen if we could sense our inner emotions in real-time and quietly ask ourselves these questions before we respond to a triggering emotion, “What is going on here? What emotion am I feeling? Am I leaning into my old habits? How can I turn this conversation around? How can we collectively explore a better option?”

Additionally, due to my upbringing, I struggled to understand my emotions – any kind of emotion was never acceptable in my home. If I couldn’t identify it, I couldn’t do anything about it either.

In my work environments, all kinds of emotions were constantly playing out in real-time, every day. Decoding them and learning how to take a better path was something I learned belatedly, but has become something I help teams work through every day.We can short-circuit and rewire our internal neuropathways with practice – Neuroplasticity.

When we feel a trigger coming inside a discussion, we have only a few micro-seconds to insert a metal rod into the spokes of our wheels by saying, “This is a good discussion, let me think about it for a while (i.e., in a hour, next day, etc.) and then let’s continue our talk to find some solutions.”

This is very hard to practice in real life, as once we have the emotion, we must turn around and facilitate a different discussion midstream. But its effects are far-reaching. In this, you are:

- Giving a timeframe to continue

- Giving both of you a de-escalation period

- Regaining the use of your prefrontal cortex (executive function) instead of your amygdala (the fight/flight/freeze/appease center of the brain: our most ancient brain)

- Giving grace and honor to the other person AND yourself, and

- Starting to craft a co-creative moment and subsequent solution for both of you.

As Difficult Colleagues ourselves, we all come with our own lenses and experiences. Let’s give each other options instead of thinking there is only a lose-lose or win-lose outcome ahead.

Experiencing our emotions means diving into how and why we think certain things, and finding better ways to work out problems between ourselves and our coworkers, whether they’re our bosses or not.